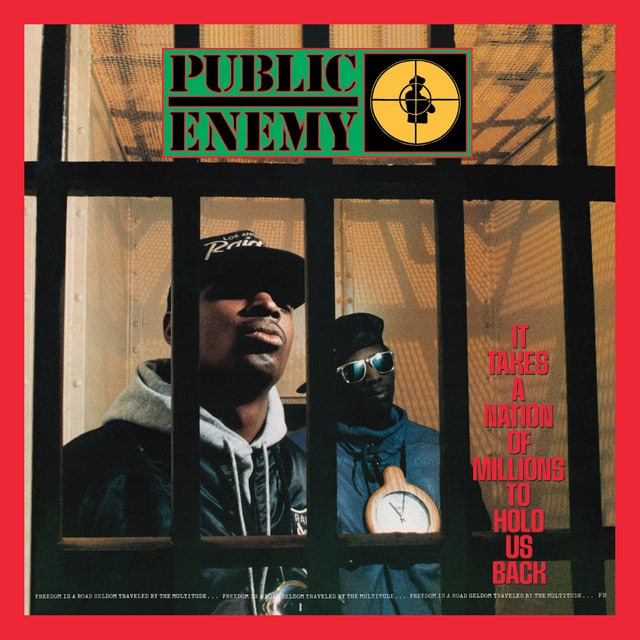

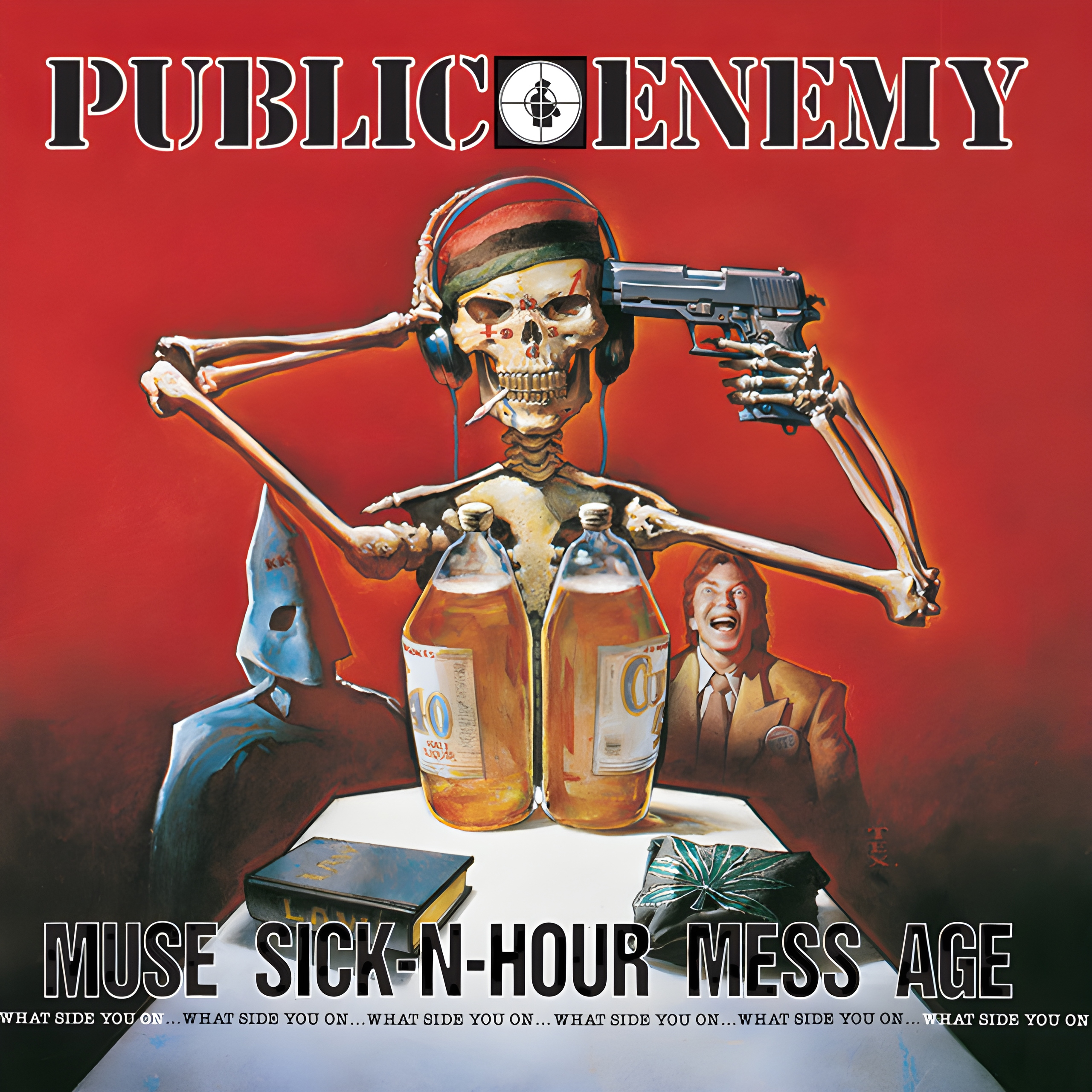

Released: 1994

Public Enemy’s “Godd Complexx” is a powerful commentary on systemic oppression and racial inequality, infused with the sharp social criticism the group is known for. The song highlights the notion of a “God complex” held by those in power, illustrating how it contributes to racial injustices and economic struggles experienced by marginalized communities.

The hook “Up, down on the corner, uptown” paints a vivid image of city life, symbolizing the common street corner where life’s challenges play out, particularly for the African American community. It’s repetitive, reinforcing the constant, never-changing presence of these issues. This backdrop sets the stage for deeper discussion about systemic inequalities.

The first verse dives straight into the harsh realities, opening with “I turn around and hear the sound of voices / Talkin’ ’bout who’s goin’ to die next,” capturing the perpetual threat of violence and death in black neighborhoods. Chuck D criticizes the ‘white man’s God complex,’ suggesting a mindset of superiority that permits oppression and indifference towards the struggles faced by people of color.

“Nigga go make your own help, shit you need it,” is a brutally honest reflection of the self-reliance often imposed on marginalized communities, implying that assistance is scarce, if ever present, and one must fend for themselves amidst systemic neglect. This statement underscores a broader critique of how society neglects certain demographics.

As Chuck D references “jukeboxes playin’ in bars” and “pimps parked outside in big pretty Flavor Flav cars,” he sketches a tableau of urban culture. These lines contrast the opulence with underlying desperation, emphasizing that the external allure doesn’t change the socio-economic circumstances – it’s all just part of the street theater.

“Cleaner than a broke dick dog” is an interesting slang metaphor expressing extreme poverty despite outward appearances. It plays into the critique of consumer culture and materialism as escapism in impoverished communities. Even while looking fly in Calvin Kani, a designer brand popular among urban youth, there’s an inescapable socio-economic cage defined by racial hierarchies.

As we delve into the chorus, “The white man’s got a God complex,” it’s a blunt denunciation of how power dynamics are skewed to favor whites over blacks. This sentiment isn’t just about race but encompasses how white-centric ideologies shape socio-political structures, often dictating life and death scenarios for minorities.

In the narrative section involving a conversation about purchasing items “black ones, brown ones… I even got a white one,” Public Enemy delves into the idea of commodification. It symbolizes how, within the racist system, everything and everyone seems to be on sale, bought, or controlled under this perceived supremacy. Even chance games reflect on life’s inequalities – “snake eyes, sorry nigga you lose.”

The line “‘Cause the white man’s got a God complex” reiterates the driving theme – how ingrained the imbalance of power is, dictating the lived experiences of marginalized communities. Chuck D goes on to express distrust and awareness in lines about reading “dream books” and his knowledge of “what I’m talkin’ ’bout.” It represents a sense of foresight about the systematic pitfalls waiting at every turn.

Closing with a powerful listing of systemic evils: “I’m making guns… I’m making free machines,” the outro verse is a blistering condemnation of how industry, government, and racial hierarchy entwine to uphold an exploitative status quo. Public Enemy questions this self-appointed godhood that exercises dominion through destruction and manipulation – from warfare to social injustice, reiterating how oppression permeates every level of existence.

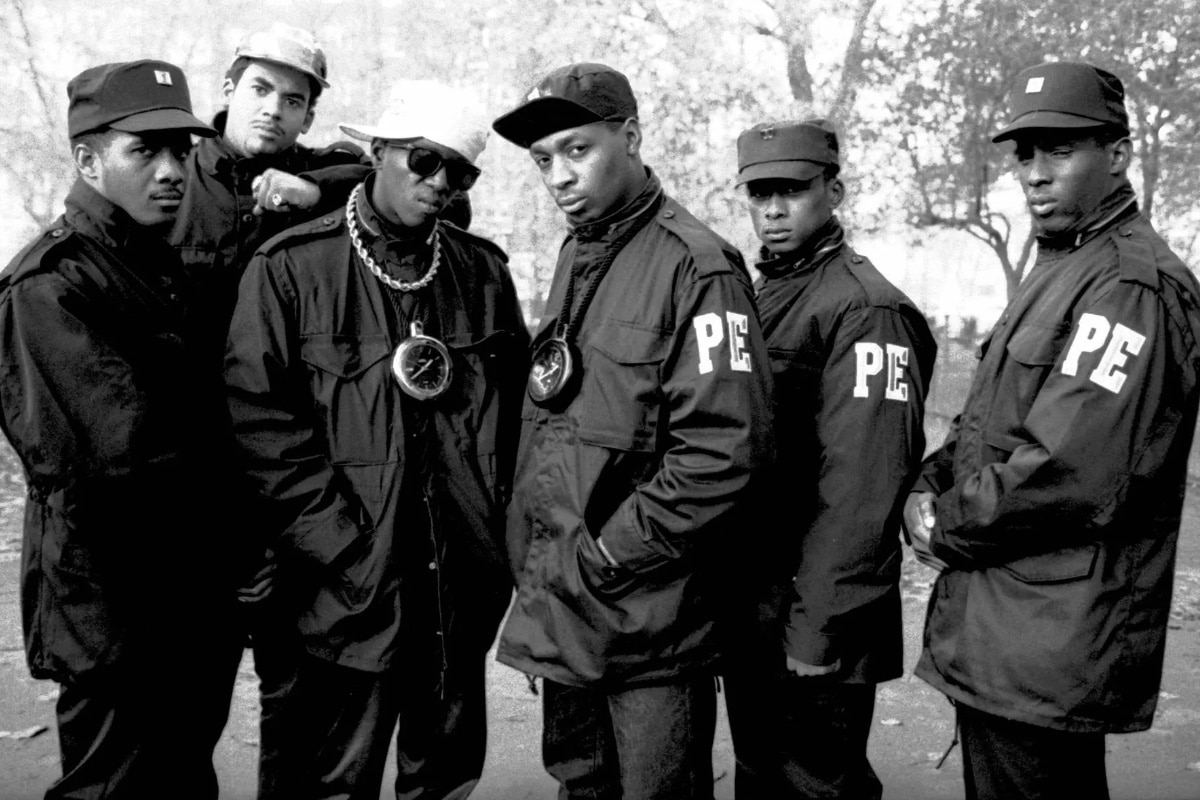

Public Enemy’s work often melds militant politics with powerful beats, using hip-hop as a platform for radical change. “Godd Complexx” stands as a potent reminder of the cultural and political landscape in which they rap – one that continues to reflect the ongoing struggle for equality and justice. In doing so, it echoes the same revolutionary messages found in other notable tracks by the group, embodying the very essence of what they represent.