Top 50 Most Streamed Hip Hop Songs Right Now

We’re tracking what people are listening to on the daily, forget Billboard and radio plays, this is what everyone’s choosing to listen to right now. This is what people are listening to right now, period.

Rick Ross’ Greatest Bangers That Go Hard

If we’re talking bars, beats, and boss-like swagger, very few can match the mighty Rick Ross. Born William Leonard Roberts II, Ross has been serving the streets and the charts with fiery anthems and contemplative slow-burners for well…

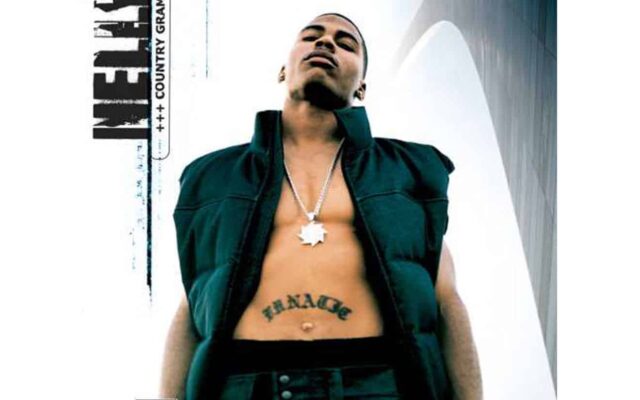

Nelly’s Greatest Bangers That Go Hard

Nelly, hip-hop’s own Midwestern powerhouse, consistently served up a sonic platter featuring the best elements of hip-hop, RnB, and pop. Bursting onto the scene with ‘Country Grammar’ in 2000, the St. Louis titan carved out a niche with…

21 Savage Songs That Go Hard

When the rap game first caught a glimpse of 21 Savage, he was blown up as the street-hardened lyricist from Atlanta, a city that’s been a focal point of hip-hop innovation. With each subsequent album, from his debut…

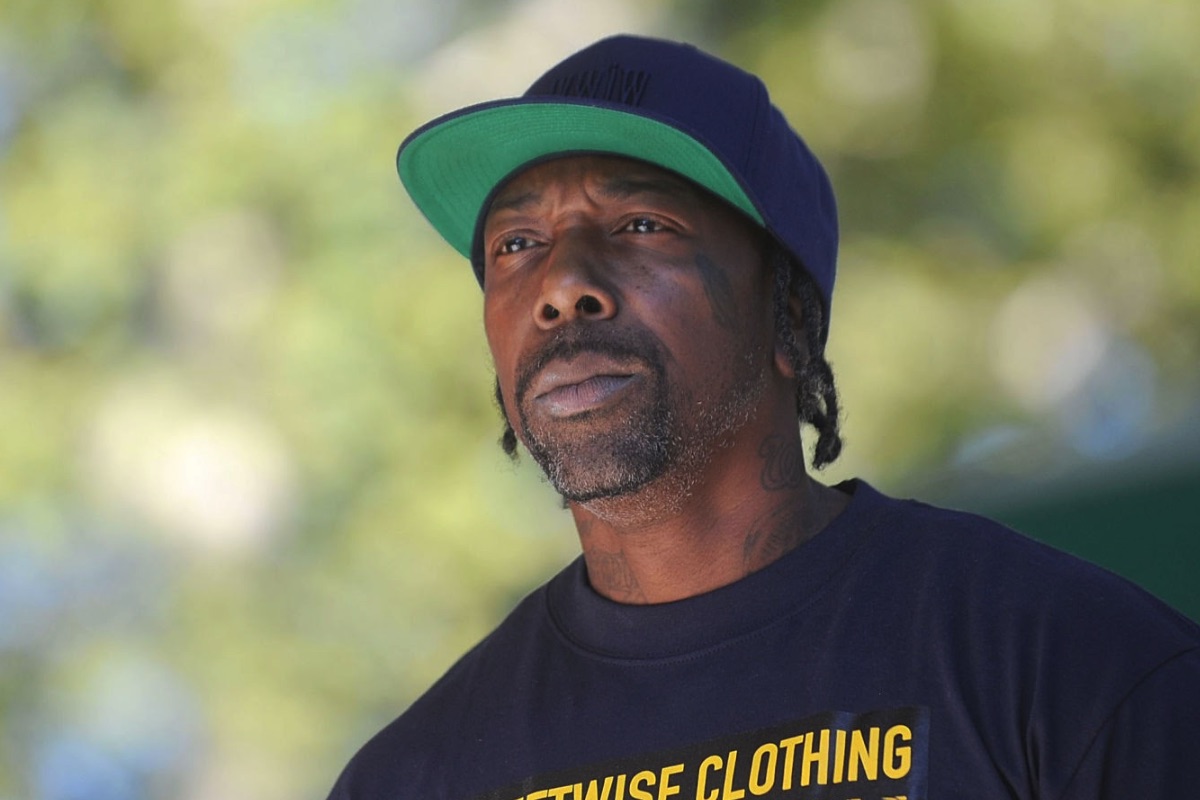

The Best of Nate Dogg’s Solo Songs

With a pedigree that includes collaborations with the heaviest of heavyweights, from Dr. Dre’s sonic landscapes to Snoop Dogg’s laid-back tales, Warren G’s regulated beats, and 2Pac’s anthemic bangers, Nate Dogg’s solo ventures often showcase his ability to…

The Best of MC Eiht’s Solo Hits

Known for his deep, baritone voice and vivid storytelling, MC Eiht has been a defining figure of the gangsta rap genre. His solo work, peppered with collaborations featuring some of the most iconic names in hip-hop, showcases a…

The Best of Ludacris’ Solo Songs Ranked by Fan Votes

From the streets of Atlanta to the top of the charts, Luda’s journey has been nothing short of legendary. His discography is a treasure trove of hits, each track a testament to his versatility, from club bangers to…

Timeline of Every Rapper Who Was King of New York

Yo, peep this: New York City – that’s where hip hop was spit into existence, where beats pulsed through concrete and rhymes were scribed on subway walls. Ain’t just about birthplace status, though. NYC, that’s the battleground where…

The Most Iconic Gucci Mane Mixtapes

Yo, forget best-of lists – Gucci Mane ain’t about albums, he’s the mixtape kingpin. Dude’s got more tapes than a trap house got scales, and every single one a brick of raw, uncut street gospel. We talking anthems…

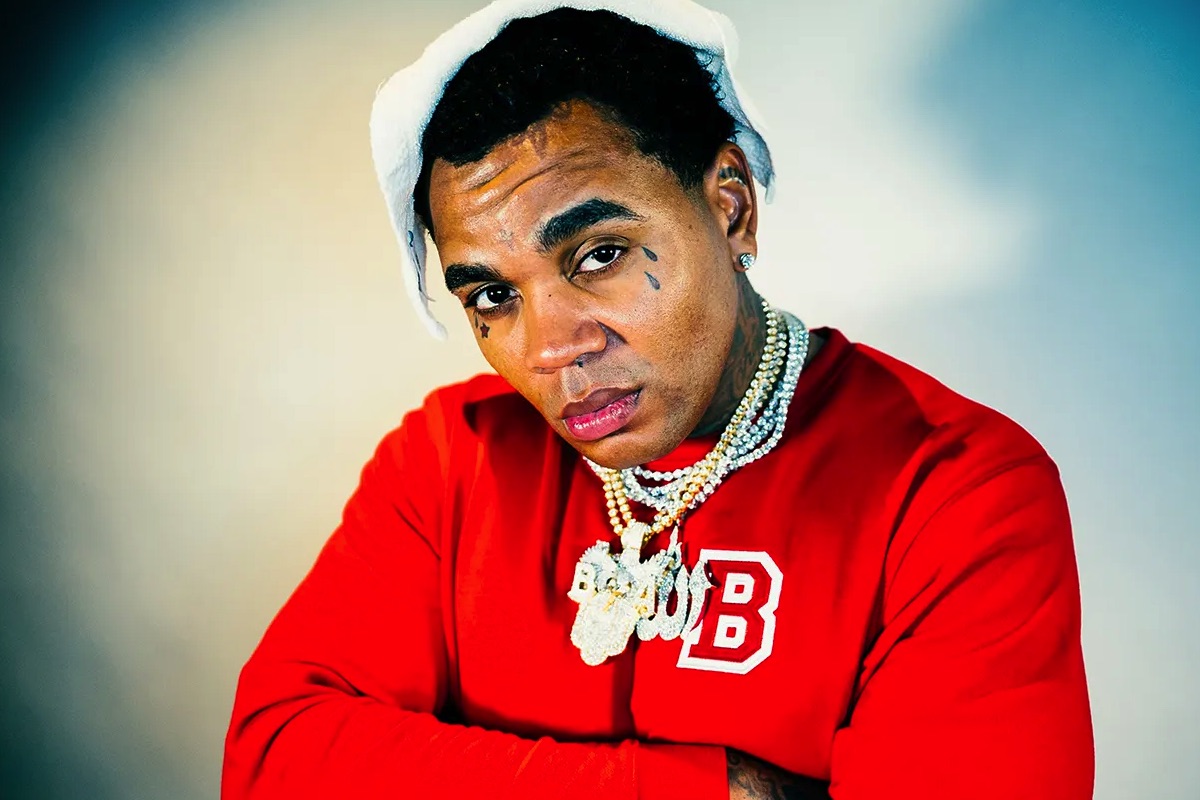

Every Kevin Gates Project Ranked by Real Heads

Kevin Gates ain’t for everybody. Dude’s raw, emotional, and often ain’t playing by anyone’s rules but his own. He gon’ tell you about his pain, his demons, his triumphs – the whole messy, contradictory truth that makes up…

Top 50 Best Rap Diss Tracks of All Time

Built on the foundation of corner block freestyles and battle rap performances, rap diss tracks have evolved to become a hallmark of the culture, a platform for lyrical warfare, and a riveting spectacle of raw emotion and competitive…

Top 50 Best Hip Hop Songs of the 2000s

The 2000s were a pivotal decade in hip-hop culture, marked by both the rise of new artists and the maturation of established acts. From New York to L.A., Houston to Atlanta, Chicago to Detroit, the rap landscape was…

The Best Canadian Rappers that are Hot Right Now

Too often folks forget about the crazy hip hop scene Canada’s got goin’ on. These past few years, cats north of the border been servin’ up beats and rhymes that go toe-to-toe with anything droppin’ in the States.…

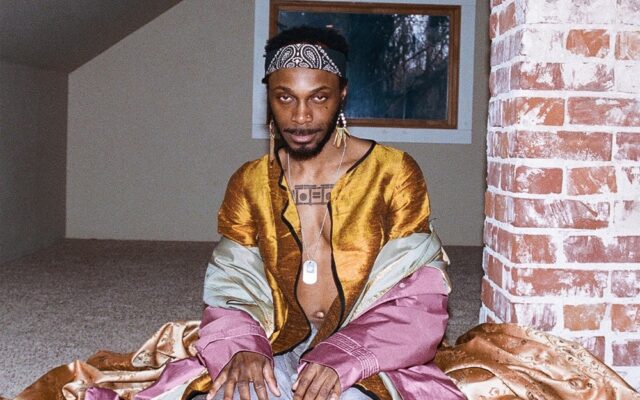

The Best Male R&B Singers That Are Hot Right Now

Today’s artists continue to push boundaries and redefine what it means to be a modern R&B sensation. The genre, known for its soulful melodies, intricate vocals, and emotionally charged lyrics, has seen a renaissance in recent years, thanks…

The Best Female R&B Singers Today

In the vast, ever-evolving universe of music, R&B holds a special place, similar to what Mary J Blige has in this genre, especially when it comes to the profound impact of female artists. Gone are the days when…

The Best Rappers from Baltimore

Baltimore, a city known for its vibrant culture and resilient spirit, has increasingly become a hotspot for hip hop talents such as Bossman that’s pushing boundaries and making waves far beyond its borders. Today, the Baltimore rap scene…

Every Fuerza Regida Album Ranked by Real Heads

Yo, you gotta check out Fuerza Regida – these cats are revolutionizin’ regional Mexican music. They ain’t afraid to get real, spittin’ ’bout love, struggle, and the grind. They keep the corridos classic, but they mix in heavy…

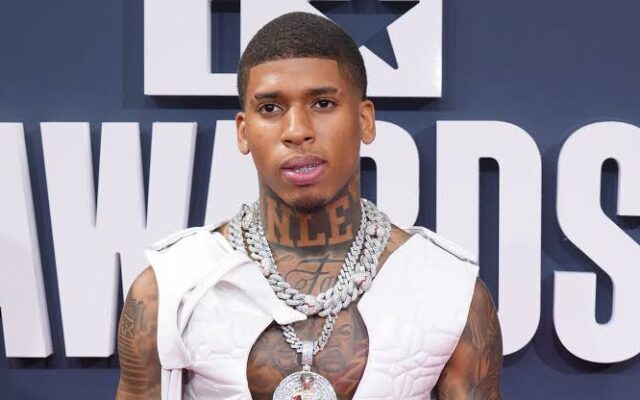

The Best Alabama Rappers Right Now

When we talk about the hip hop scene, it’s easy to get lost in the mentions of major city powerhouses like Atlanta, New York, or LA. But let’s pivot the spotlight to a state that’s been quietly cooking…

The Best Nas Albums Ranked: From Illmatic to Magic 3

Let’s talk about the king of Queensbridge, the poet with the illest rhymes – Nas. This cat dropped “Illmatic” and changed the whole damn game, forever earnin’ his spot in the hip hop hall of fame. But that…

Top 100 Legendary Rappers: A Definitive List of the Best Rappers of All Time in the Rap Game

In recent years, artists like Kendrick Lamar, Jack Harlow, Post Malone and Young Thug have emerged as the vanguard of a new generation, fearlessly pushing the boundaries of hip hop culture and paving the way for fresh talent…

The Best R&B Singers of All Time

Let’s talk R&B, the music that gets deep in your soul. This ain’t just notes, it’s the soundtrack to love, heartbreak, and the whole damn struggle. R&B got its roots in gospel, jazz, and the blues, and it’s…

Every Jack Harlow Album Ranked by Fan Votes

Aight, let’s talk about Jack Harlow – this cat from Kentucky who’s put a new spin on the game. Dude’s got that smooth flow with beats that nod to his roots, but it’s bigger than that. He’s built…

Every Usher Album

From the heart of Chattanooga to the pulsing epicenter of R&B royalty, Usher Raymond IV’s journey through the music landscape has been nothing short of legendary. This Southern prodigy, armed with a velvety voice and unmatched charisma, metamorphosed…

Every Gangsta Boo Album Ranked by Real Heads

The magnetic prowess of Gangsta Boo—the hip-hop titan from Memphis—can’t be overstated. Born Lola Mitchell, she volleyed onto the scene, becoming the only female member of the iconic rap collective, Three 6 Mafia. Over the years, Boo has…

Snoop Dogg Doggystyle: Album Rundown Every Track

Released: 1993 Featuring: D.O.C., RBX, Tha Dogg Pound, The Lady Of Rage, Nate Dogg, Warren G, Kurupt, The Dramatics A chilling blend of razor-sharp rhymes, hypnotic G-funk grooves, and iconoclastic storytelling, Snoop Dogg’s ‘Doggystyle’ is a cornerstone in…

Top 10 Rappers with the Most Grammy Award Wins

The Grammys and hip hop? That relationship’s been rocky since day one. Despite the fact that rap is the biggest genre in the world, the Grammys be playin’ catchup, always late to the party. Remember when DJ Jazzy…

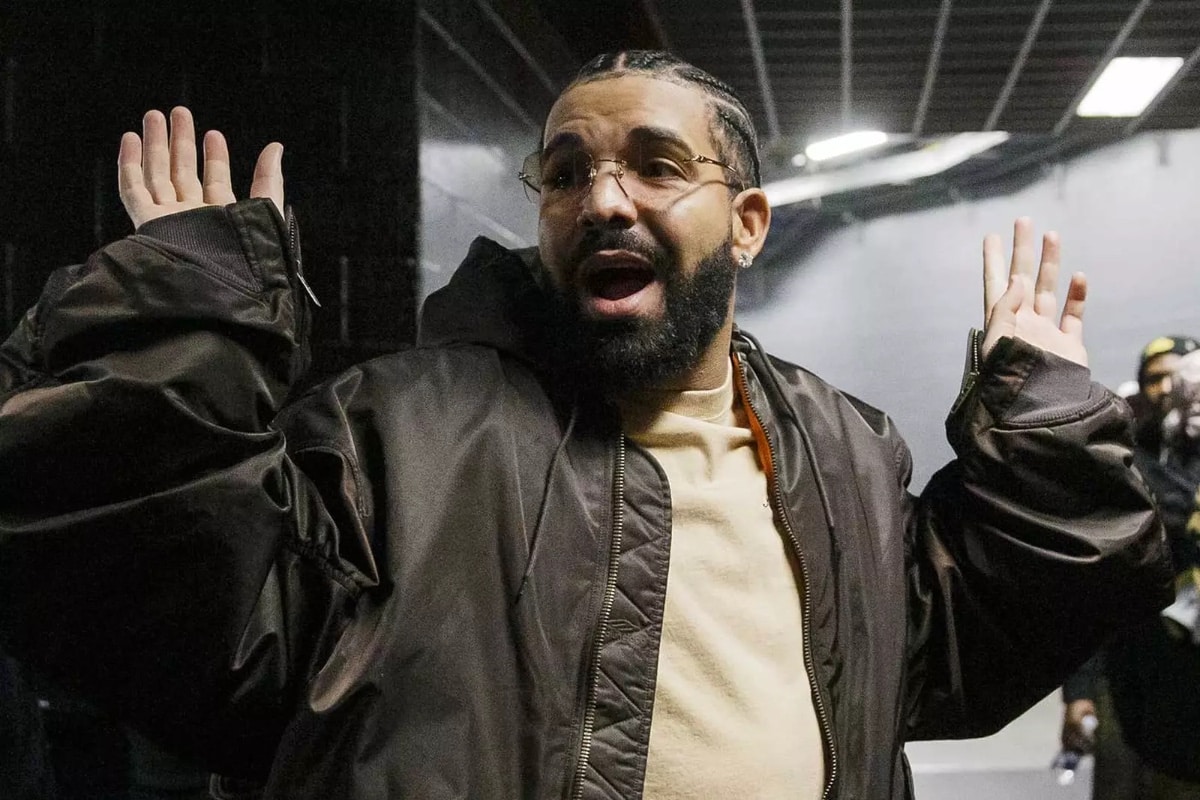

Drake Views: Album Rundown by Track

Released: 2016 Featuring: PARTYNEXTDOOR, dvsn, Pimp C, Wizkid, Kyla, Future, Rihanna, Majid Jordan From the icy realms of the Great White North emerged a contender, a shift in the tectonic plates of hip-hop. Aubrey ‘Drake’ Graham, a diplomat…

Ranking Every Styles P Album, From Worst to Best

Styles P, the inimitable voice gracing some of the hardest tracks from The LOX, is appreciated by true fans and hip-hop scholars for his solo work that zigzags between the opulent gangsta personas and introspective bars. This Yonkers…

Top 25 Best Female Rappers Right Now

In a world where hip hop’s throne is continually contested by males, female rappers have more than held their own — standing their ground and igniting the scene with fierce competition. In this epic countdown, we’ve got heavy…

Ranking Freeway’s Albums, From Worst to Best

When it comes to the hardcore rap scene, few artists have brought as much intensity, authenticity, and lyrical prowess as Philly’s own Freeway. Born Leslie Edward Pridgen, Freeway has been a consistent force in hip-hop since his introduction…

Ranking Every Kid Cudi Album, From Worst to Best

There have been few hip hop artists in the past decade who have had as much a hand in shaping the modern rap game as Scott Ramon Seguro Mescudi, aka Kid Cudi. From Kanye West, Travis Scott and…

Every Single No. 1 Hip Hop Song On the Billboard Hot 100

While hip hop had its origins in the 1970s on the New York block parties and park jams, it wasn’t until “Rapper’s Delight” entered the top 40 Billboard chart that the masses started to take notice. But even…

Every Eminem Diss Track Ranked

When it comes to the realm of hip hop, few artists have made as significant an impact as Eminem. His lyrical prowess, rapid-fire delivery, and unapologetic attitude have solidified his place as one of the greatest MCs in…

Top 10 Best Memphis Rappers of All Time

The history of Memphis hip hop is rich and complex, with a diverse range of artists and sounds that have helped shape the genre as we know it today. From the early days of DJ Spanish Fly and…

The Best Feature Rappers of All Time

When it comes to the art of the feature verse in hip-hop, it’s a whole different ball game. Think of it as a guest appearance on your favorite TV show; it can either steal the scene or flop…

Ranking Every Chief Keef Studio Album, From Worst to Best

Chief Keef, the prodigious rapper from Chicago’s South Side, has been a trailblazer in the hip-hop scene since his breakout in the early 2010s. With a prolific discography that’s an embodiment of the drill genre, Keef’s music is…

Ranking the Best 5-Year Stretches in Hip Hop History

Hip-hop has continuously evolved and reshaped the cultural landscape, with multiple golden eras. Each of those has contributed its unique flavor to the rich and colorful history. Here we are defining these moments as we embark on a…

The Best of Fat Joe’s Albums Ranked, from Worst to Best

Born as Joseph Antonio Cartagena but better known by his stage name, Fat Joe, this Bronx emcee has been a cornerstone of the hip-hop scene since his debut album “Represent” dropped in ’93. Whether he’s trading bars with…

The Best Female Rappers of all Time

In our previous endeavor to capture the essence of hip-hop greatness in a list of the all-time best rappers, we realized a glaring oversight: the underrepresentation of the incredible female talent that has graced the genre. Crafting such…

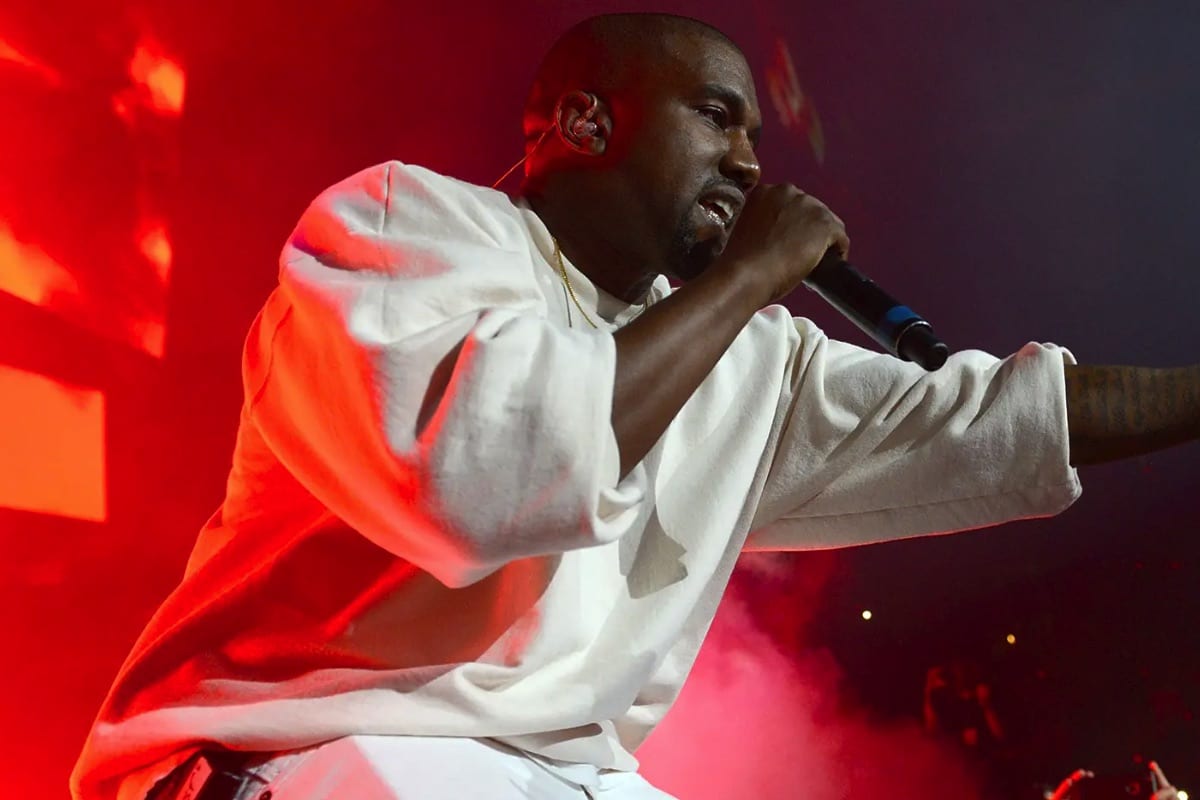

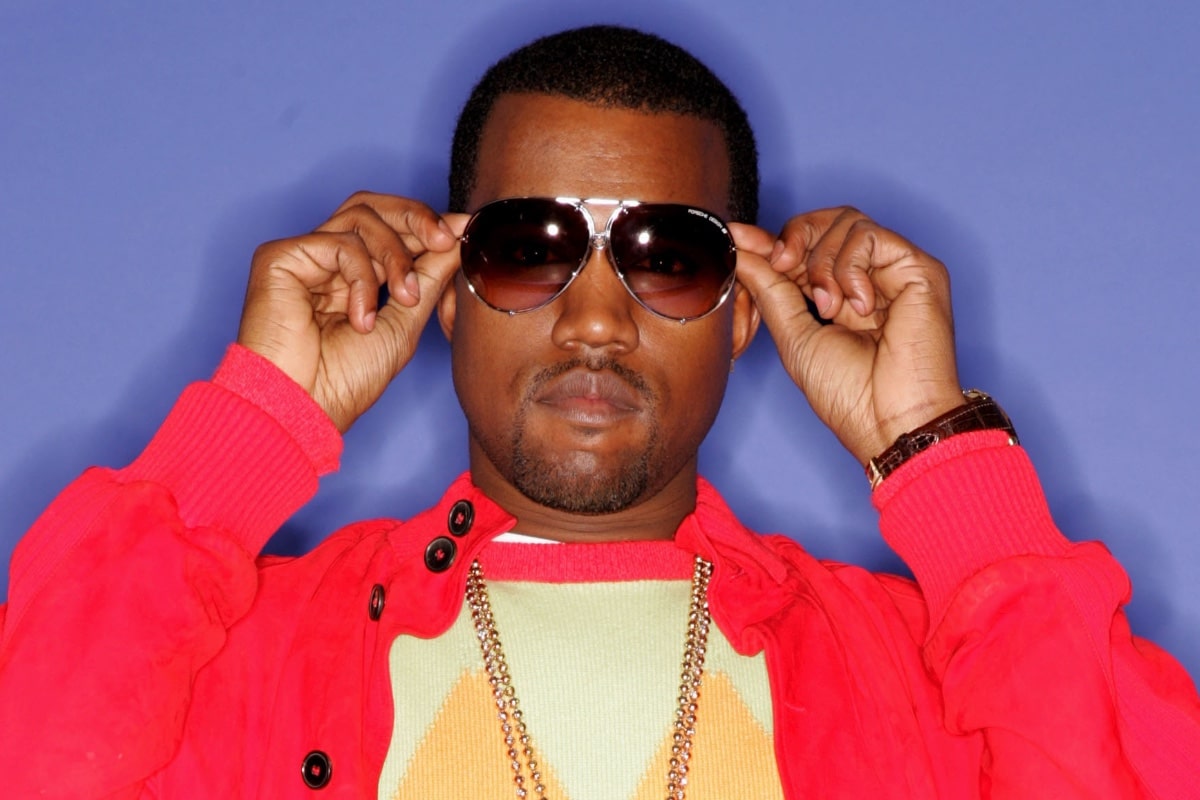

Ranking Every Kanye West Album, From Worst to Best

Kanye West, a figure as polarizing as he is influential, has indelibly shaped hip-hop culture. From his early days as a gifted beat-maker in Chicago to becoming one of the defining rap icons of our era, Kanye’s journey…

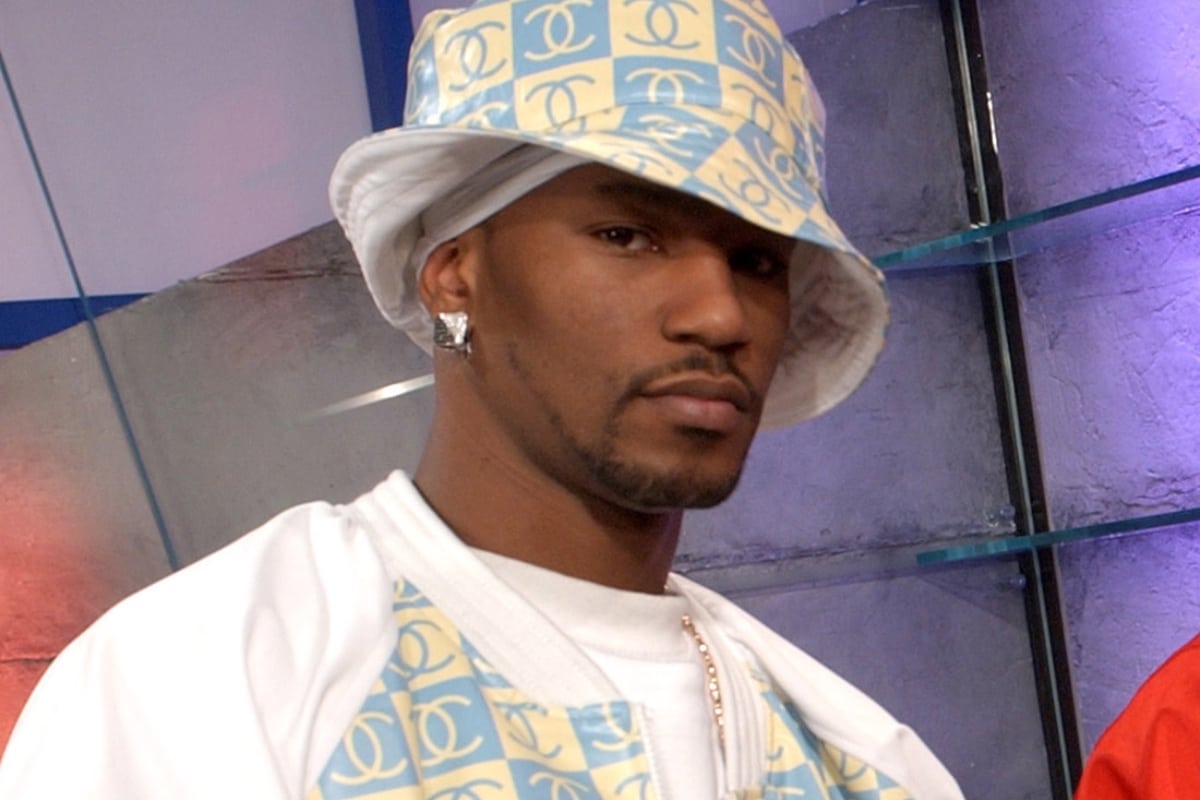

Ranking Every Cam’ron Album, From Worst to Best

Cam’ron, Harlem’s very own lyrical maestro, has cemented his legacy as one of hip-hop’s most iconic figures. From the raw streets of Uptown Manhattan, he painted a picture of the city’s hustle, blending unapologetic bravado with street tales…

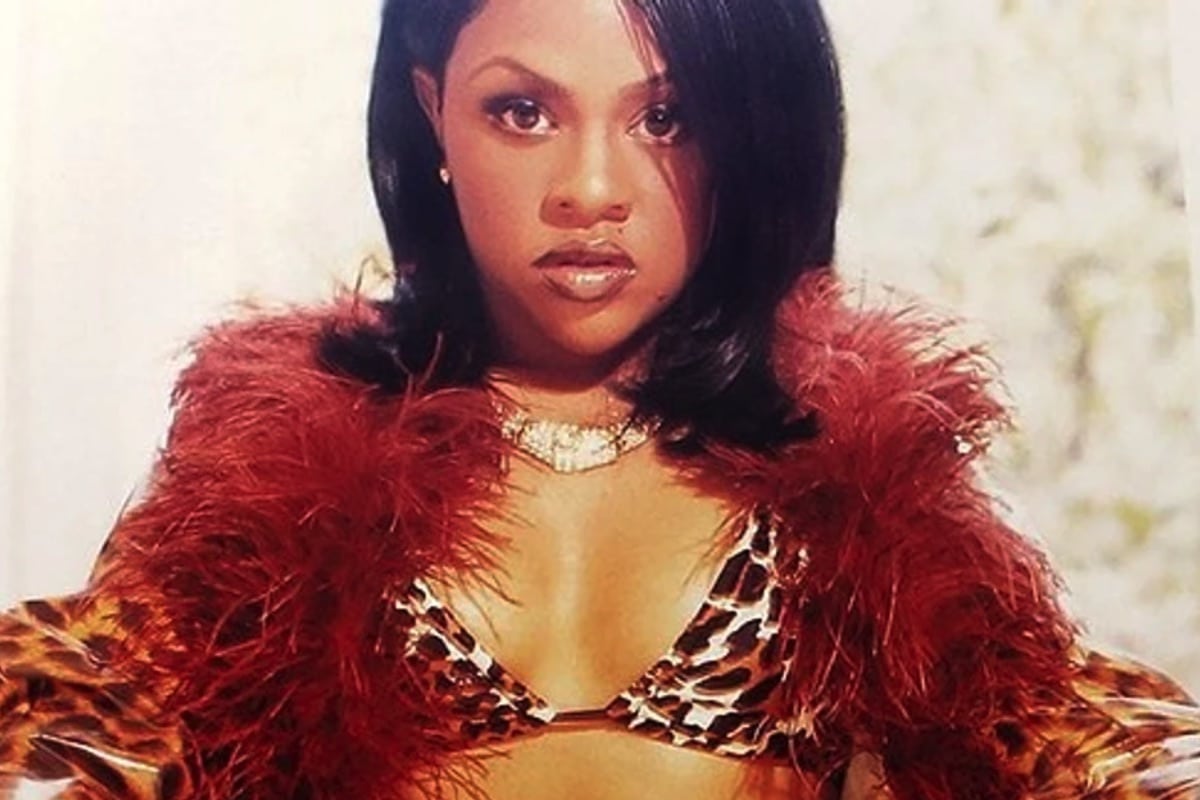

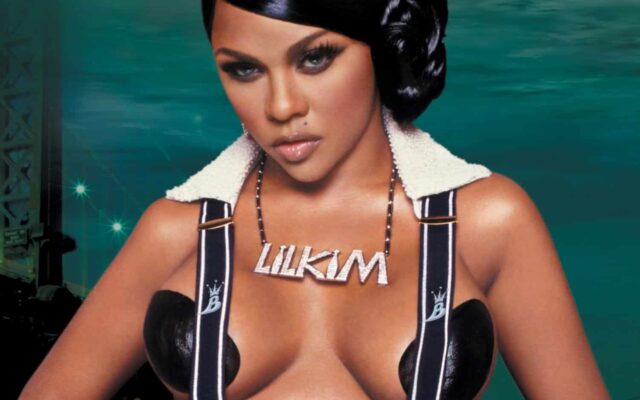

Ranking every Lil’ Kim Album, from Worst to Best

As one of hip-hop’s most iconic queens, Lil’ Kim, born Kimberly Denise Jones, stormed onto the scene in the 90s with a rawness, sensuality, and luxuriously gangsta flavor unheard before. Cutting through the male-dominated game, her albums are…

The Top 20 Best UK Rapper & Vocalist Collaborations of the 2000’s

At the turn of the millennium, UK hip-hop began to carve out its niche, pulling from the influences of its transatlantic counterpart while unmistakably branding its own sonic fingerprint. The 2000s was the era of gritty instrumentals and…

The Best White Rappers in the Rap Game besides Eminem

Besides Eminem, we look at the best white rappers that are worth listening to, including names like Logic, Macklemore, El-P, to Aesop Rock, Sage Francis & Mac Miller. Icons like the Beastie Boys broke new ground in hip-hop,…

Dizzee Rascal Albums: Ranked from Worst to Best

In the vast landscape of British hip-hop, one name stands out as a true pioneer and trailblazer – Dizzee Rascal. With his unique blend of grime, rap, and electronic beats, Dizzee Rascal has left an indelible mark on…

The 10 Most Influential Mexican Rappers

Here we’re diving into Mexican rappers, shining a spotlight on the game-changers and mic-masters who’ve put Mexican rap on the map. This ain’t just about beats and rhymes; it’s a journey through cultural expressions, street narratives, and bold,…

Ranking Lil Uzi Vert’s Albums, from Worst to Best

Step into the world of Symere Bysil Woods, better known as Lil Uzi Vert, one of hip-hop’s boldest voices. Since his breakout in 2015, Uzi has dropped a series of projects that have changed the game—not only with…